In 2008, senior Menghorn Seng moved to the United States from Cambodia with his parents and younger brother. Seng is in many ways a typical teenager, but his life varies from that of the typical high school experience. Seng is a student in the English for Speakers of Other Languages program, better known as the ESOL program.

The average student already has a lot on their plate, but Seng in particular has a huge set of responsibilities. Seng is the oldest son in his family and must be a good role model for his bother. Besides that, he was not able to speak English at all upon his arrival in the U.S., so he was in the ESOL program for more then a year.

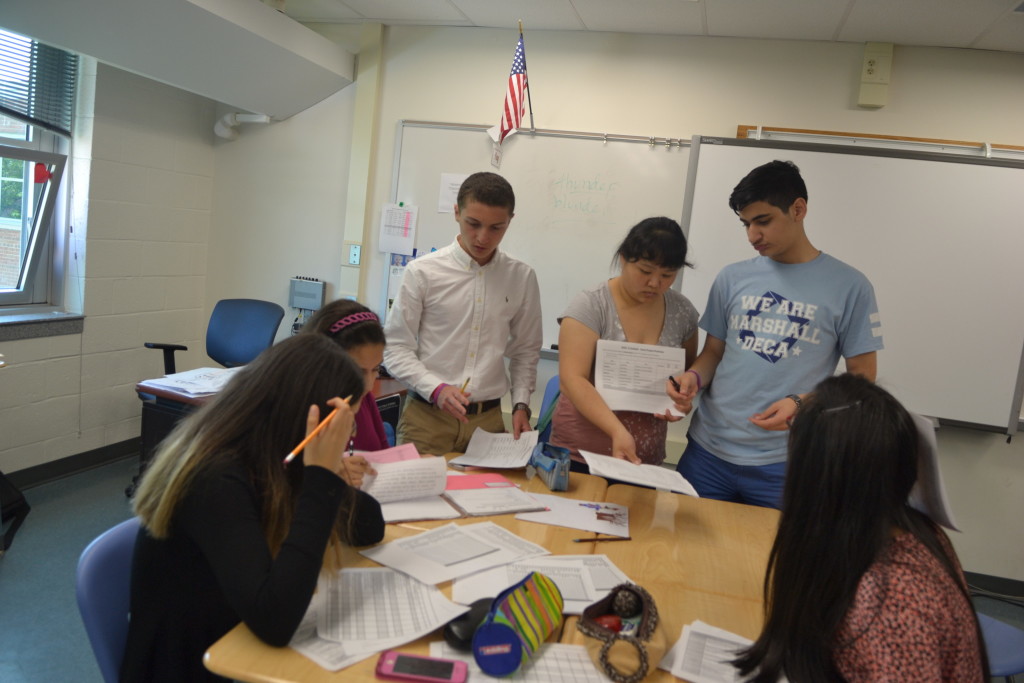

ESOL teacher Sunny Nieh, whose parents were immigrants from Taiwan, guides her students through projects that help develop their language abilities.

“They learn skills that teachers assume they have in other classes,” Nieh said.

As a member of an immigrant family, Nieh is familiar with the process and challenges of immigration. In her role as an ESOL teacher, she feels the responsibility to help her students with any difficulties they face.

Seng, unable to communicate with the cafeteria staff, was not able to buy lunch during his first year in the U.S. He spent his lunches in his classrooms, which made it hard for him to make friends.

“Everyone is separate here,” Seng said.

In the first year, he struggled and says he did not appreciate his parents’ choice to move to the U.S. Now, though, he sees his progress in learning English and in other academic fields.

“I have more opportunities in the U.S.,” Seng said.

According to Nieh, the culture shock a new immigrant must face can run deeper than many teachers realize.

“Topics like doing homework, paying attention in class and cheating are not cross-cultural and many teachers don’t realize that these are things that they have to explicitly mention and talk about,” Nieh said.

Many ESOL students don’t ask questions because they don’t feel confident enough with their language skills, leading to misunderstandings.

“They just assume that it works the same way as in their school throughout the country. In content classes there is no time to talk about that because it is so IB- and SOL-driven,” Nieh continued.

Thus, ESOL is not only a class that teaches grammar and vocabulary. It also also helps students adapt to life in the U.S. and explore their academic goals.

“You are not only teaching them information, but also how to be successful in America, because their experience is different,” Nieh said.

Seng, for example, discovered his interest in engineering through his ESOL class.

“I want to work in engineering or mechanical fields after I finish studying,” he said. “Once I make a good amount of money I want to buy a house for my family, send money to my relatives back in Cambodia and of course get a good sporty car.”

As he adjusted to life in America, Seng had to delay graduation.

“I was asked why I was at Marshall for more than four years and people would not understand that some have different life situations that makes someone’s life harder than others’,” Seng said.

Immigrants sometimes have to leave spiritual and material things behind to build up a better life.

“I left many things behind: my family, the farm that we lived on with my animals and the opportunity to graduate at 18. But I get back what I give,” Seng said.

Seng has gotten support from his ESOL class and is hopeful about his future in America. But he says if he could make the move again, he would change some of his choices as a new immigrant.

“If I went back to when I first got here, I would instead go to an adult high school so I could manage my life more easily as I was working,” Seng said.