By the time students have graduated from high school and are ready to begin their college education, one of the last things they want to be doing is getting stuck in introductory-level classes with hundreds of other students.

While enrolling in college-level courses in high school might be a sound solution, many students taking IB level classes do not receive the same college credit as their AP peers, and are forced to take the same introductory-level classes as the students who never took higher level classes in high school.

“The main problem has been just lack of awareness, among not the universities themselves, but among the departments,” IB coordinator Carlota Shewchuk said.

This issue shifts from being an inconvenience to raising the question of fairness when the treatment of IB students is compared to the treatment of AP students.

While the scores needed to gain college credit vary by university and with each course, the common trend is that while colleges accept 4s and 5s from AP exams, which are scored out of 5 points, they usually only accept 6s or 7s on IB exams, and for math and science courses they usually only take 7s.

It may seem fair that colleges take the top two scores from each scale, but looking at Total Registration’s reported scores for AP physics C and the IB Organization’s reported scores for IB physics SL, for example, reveals that while 32 percent of AP students got the highest score on the exam, only eight percent of students received the highest mark on the IB exam.

“I feel let down,” junior Robert Collie said. “I’m doing all this work and I feel cheated by the colleges.”

Virginia did pass a law in 2010 forcing public state universities to consider IB and AP equally for college credits, but colleges still get around it by requiring scores from IB students that are more difficult to obtain than those required of their AP counterparts.

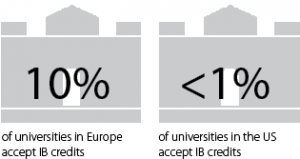

“IB has been growing in the past 11 years, and IB credit has been steadily gaining ground on AP credits, but it still has a long ways to go,” College and Career Center counselor Gardner Humphreys said.

Humphreys blames the difficulty of recieving college credits on what he calls a “history and bureaucratic inertia.”

“In other words, [colleges] started out with AP credit and the AP exams, and they’re really familiar with them,” Humphreys said. “And then as IB has grown, the number of universities that accept IB credits hasn’t grown at the same rate as the number of high schools adopting the IB curriculum.”

Shewchuk also told the story of a Marshall graduate who received a 7 on the IB English HL exam, only to discover that the University of Virginia’s policy would still not exempt her from an introductory-level English class.

The process of receiving college credit also might not be as black and white as it seems.

“Sometimes universities prefer to have polices where students advocate for their own credit,” Shewchuk said. “And students should go in with an open mind, ready to explain and show some evidence.”

Shewchuk also believes that much of the burden of changing the system relies on IB graduates.

“Every year we convince graduates to go to their universities, to the departments, to the faculty where they’re hoping to get credit, and the more they speak on the behalf of IB credits, the more things will change,” Shewchuk said.