To hear the experts talk, sleeping is the holy grail of all health problems. The National Sleep Foundation warns that too little sleep can cause you to “forget important information like names [and] numbers,” and worsen acne. The Guardian links lack of sleep to depression, high cholesterol, obesity, flu, colds and gastroenteritis. And mayoclinic.org warns of drowsy driving and difficulties learning and concentrating–an effect that, unsurprisingly, leads to trouble with “stay[ing] awake in class.”

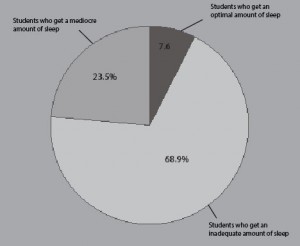

While recommendations vary as to how much sleep teenagers really need, the Virginia Academy of Sleep Medicine says at the ideal is at least nine hours of sleep per night. By contrast, the Children’s National Medical Center experts commissioned by FCPS report that 55 percent of seniors get less than six hours of sleep every night.

FCPS has been debating new high school start times designed to allow teens more sleep. But beyond the cost and the logistical problems, the real question about the proposals is: would they work? Would additional sleep substantially benefit high schoolers?

To find out, I decided to conduct a (very un-scientific) experiment: for one week, I would try to sleep for eight hours every night.

How It Went

I ran into some immediate problems: on the first night of the week, I experienced insomnia for a few hours, and a late-evening choir rehearsal kept me up until 11 a few nights later. I still managed a solid eight hours of sleep for five nights of the week, and seven hours another night, a vast increase over my usual few harried hours of post-homework rest.

Did It Work?

So what did I notice? For one, my usual late-afternoon energy drop never went away; I still found myself crashing around four or five, unable to focus on anything but a nap.

But don’t knock the value of extra sleep: my in-class drowsiness was noticeably less dramatic, which probably helped me get more out of my classes. I found an in-class essay and an IB exam to be far less daunting tasks when I wasn’t busy debating the merits of taking a power nap on my desk, and setting a strict bedtime forced me to actually start some of my homework before eight p.m.

What Difference Did It Make?

My experiment was too short-term to demonstrate substantial mood or behavioral changes, and I was still combating a massive sleep debt, a result of a months-long heavy workload and a chronic tendency toward procrastination.

My experience has definitely changed how I feel about FCPS’s schedule proposals: before, I was staunchly in support of a later start time; now, I’m not sure. Extracurriculars are a huge problem for sleep schedules—with numerous sports teams sharing a few fields or after-school theatre rehearsals, to name a few examples, reducing the number of hours available for homework, most students will probably end up sleep-deprived no matter what time they wake up.

Sleeping more did make me feel better during the day—but not as much better as I’d thought it would. To be honest, I probably won’t continue to sleep that much; it’s too much of a hassle and, not infrequently, impossible.